take this petition into consideration

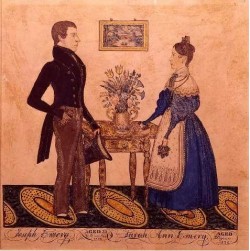

Women were recruited by officers and surgeons during the American Revolution to nurse the wounded. While the service of many nurses was acknowledged, some were not paid their due.

Alice Redman, a nurse during the War, whose pay was meager at best, but whose generosity and sense of duty were enormous, petitioned the Governor and Council of the State of Maryland around 1780 for expenses she had incurred during her service.

To the honourable the Governor and council, the Humble Petition of Alice Redman one of the nurses at the hospital [like the one shown in Yellow Springs outside Philadelphia in 1755] and your petitioner in duty Bound will Ever Pray.

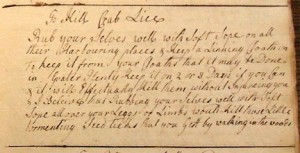

P.S. She your petitioner out of that two dollars pr. month is oblige to buy brooms and the soap we wash with if your honors will please to relieve your petitioner your petitioner will ever be bound to pray

Records indicate that Redman was reimbursed March 28, 1781.

George Washington issued instructions for nurses. They were to

• administer the medicine and diet prescribed for the sick according to order;

• be attentive to the cleanliness of the wards and patients, but to keep themselves clean, they are never to be disguised with liquor;

• see that the close-stool or pots are to be emptied as soon as possible after they are used …

• see that every patient, upon his admission in to the Hospital is immediately washed with warm water, and that his face and hands are washed and head combed every morning …

• [sweep] their wards … every morning or oftener if necessary and … [sprinkle them] with vinegar three or four times a day …

• [never] to be absent without leave.