When I was a student at Barnard in the 50s, I had the opportunity of attending lectures at Columbia by Henry Steele Commager. I was thrilled because the two-volume work The Growth of the American Republic by Commager and Samuel Eliot Morison was my favorite history of the United States. The accompanying volume of primary sources, The Spirit o f Seventy-Six, was, and still is, impressive, although few women are represented. Below is one of the entries by a woman from Philadelphia—she is anonymous—responding to a friend, a British officer in Boston, who had written a letter to her husband following the battles of Lexington and Concord. “C. S.” assures him that though he may be a public enemy he will continue to be a private friend. She gives a good summary of the various actions the Patriots, both military and civilian, were undertaking. Women doing their share, on their own and pressuring the males in their lives to act.

Sir—We received a letter from you—wherein you let Mr. S. know that you had written after the battle of Lexington, particularly to me—knowing my martial spirit—that I would delight to read the exploits of heroes. Surely, my friend, you must mean the New England heroes, as they alone performed exploits worthy fame—while the regulars, vastly superior in numbers, were obliged to retreat with a rapidity unequalled, except by the French at the battle of Minden. Indeed, General Gage gives them their due praise in his letter home, where he says Lord Percy was remarkable for his activity. You will not, I hope, take offence at any expression that, in the warmth of my heart, should escape me, when I assure you that though we consider you as a public enemy, we regard you as a private friend; and while we detest the cause you are fighting for, we wish well to your own personal interest and safety. Thus far by way of apology. As to the martial spirit you suppose me to possess, you are greatly mistaken. I tremble at the thoughts of war; but of all wars, a civil one: our all is at stake; and we are called upon by every tie that is dear and sacred to exert the spirit that Heaven has given us in this righteous struggle for liberty.

I will tell you what I have done. My only brother I have sent to the camp with my prayers and blessings; I hope he will not disgrace me; I am confident he will behave with honor and emulate the great examples he has before him; and had I twenty sons and brothers they should go. I have retrenched every superfluous expense in my table and family; tea I have not drank since last Christmas, nor bought a new cap or gown since your defeat at Lexington, and what I never did before, have learnt to knit, and am now making stockings of American wool for my servants, and this way do I throw in my mite to the public good. I know this, that as free I can die but once, but as a slave I shall not be worthy of life.

I have the pleasure to assure you that these are the sentiments of all my sister Americans. They have sacrificed both assemblies, parties of pleasure, tea drinking and finery to that great spirit of patriotism that actuates all ranks and degrees of people throughout this extensive continent. If these are the sentiments of females, what must glow in the breasts of our husbands, brothers and sons? They are as with one heart determined to die or be free.

It is not a quibble in politics, a science which few understand, which we are contending for; it is this plain truth, which the most ignorant peasant knows, and is clear to the weakest capacity, that no man has a right to take their money without their consent. The supposition is ridiculous and absurd, as none but highwaymen and robbers attempt it. Can you, my friend, reconcile it with your own good sense, that a body of men in Great Britain, who have little intercourse with America, and of course know nothing of us, nor are supposed to see or feel the misery they would inflict upon us, shall invest themselves with a power to command our lives and properties, at all times and in all cases whatsoever? You say you are no politician. Oh, sir, it requires no Machivelian head to develop this, and to discover this tyranny and oppression. It is written with a sun beam. Every one will see and know it because it will make them feel, and we shall be unworthy of the blessings of Heaven, if we ever submit to it.

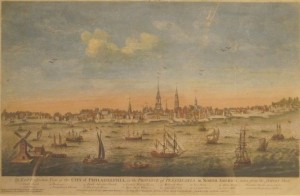

All ranks of men amongst us are in arms. Nothing is heard now in our streets but the trumpet and drum; and the universal cry is “Americans, to arms!” All your friends are officers: there are Captain S. D., Lieut. B. and Captain J. S. We have five regiments in the city and country of Philadelphia, complete in arms and uniforms, and very expert at the military manoeuvres. We have companies of light-horse, light infantry, grenadiers, riflemen and Indians, several companies of artillery, and some excellent brass cannon and field pieces. Add to this that every county in Pennsylvania and the Delaware government can send two thousand men to the field. Heaven seems to smile on us, for in the memory of man never were known such quantities of flax,and sheep without number.

We are making powder fast and do not want for ammunition. In short, we want for nothing but ships of war to defend us, which we could procure by making alliances: but such is our attachment to Great Britain that we sincerely wish for reconciliation, and cannot bear the thoughts of throwing off all dependence on her, which such a step would assuredly lead to. The God of mercy will, I hope, open the eyes of our king that he may see, while in seeking our destruction, he will go near to complete his own. It is my ardent prayer that the effusion of blood may be stopped. We hope yet to see you in this city, a friend to the liberties of America, which will give infinite satisfaction to

Your sincere friend, C.S

The letter is from The Revolution in America: or, an attempt to Collect and Preserve some of the Speeches, Orations, & Proceedings with Sketches and remarks on Men and things and other Fugitive or neglected Pieces Belonging to the Revolutionary Period in the United States by H. Niles (Baltimore: Printed and published for the Editor by William Ogden Niles, 1822), pp 505-506, which can found here. It is quoted in Commager, Spirit, 94-96.

I am sure, after the first weeks, you would like this place very well:—the city does not answer my expectation;—the plan, undoubtedly, is remarkably good;—but the houses are low, and in general, paltry, in comparison of the account I had heard. . . . We made our appearance on Thursday at the assembly. . . . the belles of the city were there. In general, the ladies are pretty, but no beauties; they all stoop, like country girls. So much for this city. . . .

I am sure, after the first weeks, you would like this place very well:—the city does not answer my expectation;—the plan, undoubtedly, is remarkably good;—but the houses are low, and in general, paltry, in comparison of the account I had heard. . . . We made our appearance on Thursday at the assembly. . . . the belles of the city were there. In general, the ladies are pretty, but no beauties; they all stoop, like country girls. So much for this city. . . .